Who do we worship?

By Hallie Ringle

In 2014 the comedian Chris Rock hosted Saturday Night Live, and during his opening monologue, which just so happens to be one of my favorite stand-up performances ever, he said:

“It’s America. We commercialize everything. Look what we did to Christmas. Christmas! Christmas is Jesus’ birthday. It’s Jesus’ birthday. I don’t know Jesus. But from what I’ve read, Jesus is the least materialistic person to ever roam the earth. No bling on Jesus. Jesus kept a low profile, and we turned his birthday into the most materialistic day of the year. Matter of fact, we have the Jesus’ birthday season. It’s a whole season of materialism. Then, at the end of the Jesus’ birthday season, we have the nerve to have an economist come on TV and tell you how horrible the Jesus birthday season was this year. “Oh, we had a horrible Jesus’s birthday this year. Hopefully, business will pick up by his crucifixion.’”

Nearly a decade after Rock’s performance, artist, painter, sculptor, filmmaker, curator, and educator John Fields created a new series of works that, similar to Rock’s monologue, employ wit and humor to reveal contradictions deeply embedded in Christian culture. Looking purely at his practice, this series is a radical departure from his earlier practice of large-scale portraiture. Yet, for those who know him, these works are physical manifestations of Fields’ struggle with capitalism and Christianity. Each object in this series complicates our understanding of religion, and for Fields, this comes from his familial connection to spiritual practices in rural Alabama. As the grandson of a Southern Baptist preacher, Fields has a deep firsthand knowledge of the culture he now critiques. In concept and in practice, this work avoids the pitfalls of the didactic and, instead, confronts larger societal issues around the instrumentalization of religion for personal and political gain.

For full disclosure, I am not Christian, and I didn’t grow up in a religious household. I did, however, grow up in the Bible Belt, where churches seem to outnumber residents. Some of the city's poorest areas were also home to new megachurches, largely funded by those living around it. And it’s this culture, this Christianity via conspicuous consumption, that led Fields to make his latest body of work. Fields’ use of readymades with charged cultural associations places him within a lineage of artists like David Hammons, who subtly transform unassuming objects into critiques of social structures. In his prints, paintings, sculptures, and performances, Hammons uses Kool-Aid, records, paper bags, and basketball hoops to deliver tongue-in-cheek challenges to racial stereotypes and economic disparities. Fields’ sculptures employ a similar confrontational yet witty tone using clocks, collection plates, coloring books, and a child’s toy hammer. For example, in Prosperity Gospel Fields uses church offering plates as the base of his works. Fields transforms these dishes, once used to collect tithes from churchgoers, with portraits of the five wealthiest American pastors. Though they remain unnamed in the work, the title reveals their net worth, thereby suggesting that they prioritize wealth over their religious beliefs. This disjunction between the pastors' professed values and their actions serves to highlight the absurdity of prosperity theology, questioning whether these pastors believe in God or the dollar.

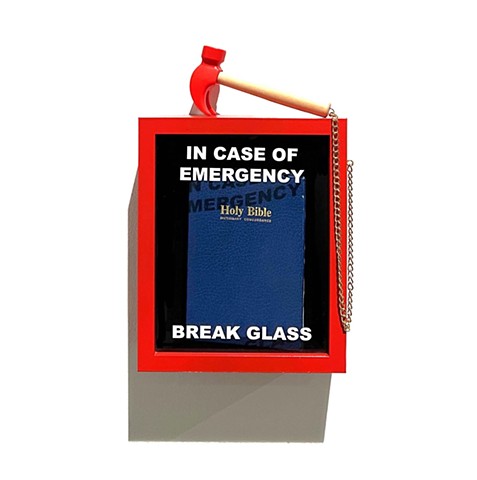

The exhibition’s titular work, In Case of Emergency, Break Glass, reimagines commonly found glass cases that house fire extinguishers. Rather than a fire extinguisher, we find Fields’ childhood bible, rendered wholly inaccessible by the case and the child’s toy plastic hammer chained to the side of the box; it carries the appearance of a tool but, in reality, is useless in an emergency. The structure of the work itself, the bible as a surrogate for a fire extinguisher, mirrors the absurdity of prayer as substitute for action. Too often, we see elected officials choosing to turn to prayer than take meaningful steps against the all-to-real sins that they can help prevent. From mass shootings to women’s rights to insurrection, Fields reminds us that prayer can’t be our only savior and has proven an insufficient substitute for action. This plastic hammer suggests action on the part of the viewer that renders any passive viewing impossible. Yet, by being unable to take the requested action and break the box, the viewer is made acutely aware of this helplessness.

In Case of Emergency, Break Glass isn’t the only work in the show to suggest the potential for action. Vacation Bible School: Jesus Heals the Blind Man is a page reproduced from a coloring book showing a scene from the Gospel of John. In this particular scene, Jesus is shown restoring vision to Celidonius, a blind man. Fields enlarged the coloring book page and created three editions of the work, each of which is reproduced by hand on canvas and accompanied by a fresh set of Crayola® crayons. Similarly, Paint Your Own Masterpiece Series: MAGA Jesus Edition is a paint-by-number kit of Jesus staring (at what?) in the distance, wearing a MAGA hat. As an edition of 25, each screen-printed canvas work comes with everything (paint sold separately) to complete the work. By providing the materials required to complete the work, Fields places the responsibility of finishing the piece on the audience. At the same time, the act of deconstruction reduces the work to its most basic components, namely canvas and pigment (paint or crayons). Through this approach, Fields symbolically dismantles the power of the church and those who invoke it for personal or political gain. While humorous, the Paint Your Own Masterpiece Series: MAGA Jesus Edition exposes the instrumentalization of Jesus by the far right and the commercialization of Christian iconography. Similarly, Vacation Bible School: Jesus Heals the Blind Man, surfaces very real questions about consent and the various methods of religious indoctrination.

In dialogue, these objects provide a clever, insistent look at the hypocrisies deeply embedded in Christianity. Using a bible, a collection plate, a coloring book, Fields exposes the irony of co-opting Christianity for personal gain, whether that’s monetary or political gain. This deliberate use of materials poses probing questions about religion and its far-reaching influences beyond that of a single church or pastor, forcing us to ask, are we (they) worshipping God or capitalism?

Hallie Ringle is the Daniel and Brett Sundheim Chief Curator for the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania.